Welcome to The Future of Nothing, a sci-fi collection set in the 2040s, in a world forever changed by climate disaster. Still, my goal is to look at humanity from a place of hope – imagining a world where we finally live in harmony with nature, becoming who we’re truly meant to be.

You can find this collection in e-book form (with a bonus novella), but I wanted to make this webpage where you can experience this world and find additional resources / ways to get involved. I also write a silly little Substack, The Carbon Fables, where you can get ongoing climate content. Enjoy!

The Bridge

I steered my little boat around the scrum of other ships, only one hand on the wheel as I hurried through a hasty breakfast. I hadn’t exactly had time to stop, but it wasn’t often my work took me through the Mackinac Straits, and I wouldn’t have been able to forgive myself if I hadn’t grabbed a pastie. Now that so many people lived up here, you could get flavors I could have only dreamed of growing up.

That morning, I’d grabbed a particularly good black daal. I’m sure my great-grandfather would have thought them a sacrilege against the pasties of his youth — he refused to budge from beef or chicken — but then again, immigration begets innovation. Pasties wouldn’t even be here without Cornish immigrants in the 1840s, and I wasn’t about to forsake my taste buds for some misplaced sense of propriety. Besides, I’m pretty sure my Poppy wouldn’t have thought his great-granddaughter could be a boat captain, either…

A coast guard trawler passed me on the starboard side, letting out a friendly double honk. Tossing back the last of my pastie, I honked back, turning the wheel as I headed for the bridge. I was getting plenty of friendly honks now with the Census emblem painted on my hull. Not everyone had been friendly when I started asking questions, but people in the straits sure were, especially now that I’d started running supplies as I made my rounds. With accurate carbon pricing, it wasn’t like you could do overnight shipping anymore.

Today, though, I had official government cargo, laden down with vials of the new antibiotics coming out of Traverse City. They’d be excited to see me at the hospital on the island, the biggest in the region now, though hopefully the residents would feel the same. I’d been making my way up the northwest coast for months, and even with my incredibly winning smile, I’d had more than a few doors slammed on me. Not that I could blame them… The losses we’d all been through were so incredibly personal. Who was I to turn their loved ones into statistics?

And yet, there was power in statistics, too. For me, there was hope in finding out how many people were alive, even if it also involved finding out how many people were dead. Besides, with the rebuilding underway, it was about time we did a census. Even if it was 2042, we certainly hadn’t been able to do one in 2030, and a lot had happened over the past twelve years. Just looking at the coastline, you’d be a fool not to notice.

There were thousands of new buildings dotting the hills of Mackinaw City. Even as the water had risen, pushing the coast back, they were all full of families who’d heard about the growth in the region. We had plenty of refugee towers, of course, but now people were just coming to work, excited about the new orchards they were putting in as the climate stabilized. Even though we were only a quarter of the way through the census, there had to be at least a million people here between Emmet and Cheboygan County. Just a casual twentyfold increase from before the crisis… Even if the estimates were right that the country’s population had been cut by two-thirds, it was astounding. Now we just had to figure out who all was there.

I passed by the northern district’s carbon towers, the blue lights still blinking in the early morning sun. I began to turn my wheel again, the towers my final reminder to start following the channel markers more closely. Traffic had quadrupled in recent years, and if I didn’t stay between the buoys as I approached the island, my little rig would no doubt be swallowed by the dozens of freighters passing through.

I went under the bridge, my boat entering its shadow. The whoosh of trucks sounded overhead, pushing over the metal grates as their drivers headed to the UP. The trucks felt almost too close now with the rise in the water level, but it felt good to pass beneath them all the same. Even after everything we’d been through, the bridge still stood after ninety years, a vital artery in the new heart of civilization. Though it was funny to think my home could be so vital to the recovery. It must have been what it had felt like in the copper boom of the 1800s, when they’d almost put the capitol up here, the last time our population had rivaled Detroit’s.

I followed the blue buoys, their blinking lights guiding me north toward the island. The waters were calm for the moment — the winter storms finally subsided — though the winds were strong, the massive wind farm off of Bois Blanc a blur of white as the turbines spun. Though I couldn’t complain. The wind was what made the hospital such a hub. Even if an island would have been inconvenient twenty years ago, the regained supremacy of boats ensured it was one of the easiest places to reach in the region.

I finally reached the docks, the concrete stretching out from the fort. I used to come here as a girl, and it still baffled me to look down through the crystal-clear waters at the remains of the old downtown. I remembered walking there with my gran, intent on avoiding the shops full of fudgies as she dragged me to the oldest one on the island. Actually, I’d just heard the week before that someone was making fudge again — the chocolate imports finally stable enough — and I made a note to hunt it down. After a hundred and forty years of making fudge — with a forced break in between — it’d be rude not to eat it.

The dock sergeant noticed me coming in, flashing a light on the military section on the west end. I pulled into a slip in the middle, a dockhand jumping on board to tie me off. I switched off the engine, putting my coat back on as I opened the cabin door.

“You’re the one with the antibiotics, right?” the sergeant asked, shaking my hand as I climbed onto the dock.

“Sure am,” I said. “Though I’ll need a two-day pass, lots of questions for the Census Bureau.”

“No problem,” he said, scratching out a pass for me.

He tore it from a pad, the little blue piece of paper scribbled with the dates I’d be allowed to stay on the island. Two days felt incredibly short after all that sailing, but I wasn’t about to complain. Plenty of boats would be coming behind me, and I wasn’t about to hog the island.

It took another hour of wrangling with the dockhands — and a kerfuffle with the hospital workers who’d run down from the hospital behind the fort — but finally, I was free to wander on my own. I headed for land, the horse-drawn wagon they’d sent for the antibiotics clearing a path for me.

Behind the old white stone of the fort, the new city stretched into the sky. Miraculously, it housed nearly ten thousand people, the island’s population of humans finally above that of its horses, though they’d at least managed to keep cars banned. I mean, what would you do with a car anyway? The island had lost two miles of its mere eight-mile diameter from before, and with the old forests thankfully still protected, there’d hardly be anywhere to drive a car, let alone park it.

I started up the new main street, the shops all full of people as the road wound its way up the limestone cliffs. At some point, I’d just start asking questions. Our records weren’t good enough for me to seek out specific houses, but at this point, I was just trying to confirm the population we’d guessed from the voucher system anyway.

But I wasn’t really in any kind of rush either. I’d sleep on the boat like always, so I didn’t have to try and find a place to stay, and the sun felt good against the dark blue of my uniform. But more than anything, it just felt good to be around so many people again. My questions were always a bit morbid — how many had been lost from each household, how they’d died, and so many other terrible things — but for the moment, I could bask in the present, surrounded by the living.

“Hey there,” a voice called to me.

I turned, finding a man in a white apron looking down at me from an open window. The sign above the door said it was a bakery.

“You from the census?” he asked. He looked older, around my father’s age if he’d still been alive.

“I am,” I said carefully, always ready with my best explanations — or excuses, depending on who you asked… But the man ended up smiling, pointing toward the door.

“Come on this way,” he said, “I wanna be the first one you talk to. I’ll give you some bread for your trouble too.”

“It’s no trouble,” I said, laughing. “Believe it or not, they pay me to do this, though I won’t say no to fresh bread.”

I went around the porch, a big smile on my face. Maybe the island would be easier than my other stops. After all, how could you feel bad with the breeze at your back and the clopping of horses in your ears? I had plenty of questions to ask, of course, but for once, it felt like I had answers too. Life felt good again, and more importantly, it felt like it was here to stay, whether or not I counted it.

About this story

Science vs Sci-fi

There’s a few things to parse out in this story: carbon capture, population change, and a sort of ‘re-industrialization,’ but let’s focus on carbon capture.

There’s a lot of types of carbon capture, but the one featured most prominently in these stories is direct air capture (DAC). The technology is kind of incredible — you literally grab carbon from the air and find a way to store it (often in rock, though you could also put it in cement or something else you’re going to use). Here’s an example from a Swiss company, Climeworks, on how it works.

However, it’s certainly not a technology without its detractors. One concern is that trusting technology to pull carbon out of the air will remove our incentive to stop emitting so much of it. While such a moral hazard is certainly real, it’s also becoming clearer that we’re going much too slowly on our emission reductions to hit our targets, so we’ll need to do something more aggressive.

Another problem is who’s going to be in charge of this technology. There are independent companies like Climeworks, but there’s also some very heavy investment from the oil and gas industry. It could be noble — a sign they’re also interested in transitioning — but it could also be a sign they’re trying to avoid what are still very necessary changes in our economy and way of life.

How can we change?

Part of the science fiction involved here, of course, is seeing DAC towers as ubiquitous, lining the coast as they pull carbon from the air and push back oblivion. To do that, though, we need the technology to scale. Currently, DAC can cost more than $600/tonne of CO2 captured. Recent policy support from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) included money to help grow carbon capture resources, but there’s more to be done. We can hope, of course, that at some point, we wake up to our crisis and commit enough resources to scale lots of technologies quickly, but the psychological shift to recognize where we are — we haven’t even declared an emergency on climate change yet despite growing damage — would be momentous.

Another question we have to ask ourselves is if we’re okay with building the infrastructure required to see some of these technologies through. In Iowa, for example, we’re seeing tough battles over the building of carbon pipelines to take the carbon we’ve captured and send it somewhere useful. We have to find a way to make progress while also respecting the land and groups looking to have their voices heard. Basically, how do we walk and chew gum?

Further Reading

- Read about the first carbon capture hubs under the IRA

- Read this primer from the IEA to get an idea of ways carbon can be used

- I know consultants like McKinsey have a checkered past — and ties to oil and gas companies — but they do have lots of data. Read this study on the future of CCUS (carbon capture utilization & storage)

Tide Work

The aluminum ladder felt warm under my fingers, the metal already taking to the summer sun despite an afternoon spent under the water. Still, I tried to keep my focus on the rungs beneath me. As much as I wanted to look at the lines of prehistoric rock on the wall, the ladder had been designed in a hurry, and it wasn’t graded for daydreaming.

Behind me, though, I knew the Bay of Fundy was pulling out, billions of gallons of water being leeched from the basin by the moon.

“Those tides are like eight thousand trains!” my supervisor had shouted at orientation. “Or twenty-five million horses. One wrong move, and you’ll be trampled!”

I couldn’t really imagine that many horses, let alone what kind of power they had, but I was excited to be there all the same. I’d signed up on a whim, calling the number on a flyer in the lobby of my refugee center.

I wasn’t the first to leave, of course. With all the ‘great rebuilding’ fervor everywhere, plenty of my friends had left for other opportunities. It’s not that I didn’t want a change of scenery — or more pay than the pittance I usually got for my maintenance work — but something else had drawn me here. Maybe it was the trees, some of the largest forests remaining after the fires, the pines dotting the stone like fur on the world’s back. Or maybe it was just the bay itself, a picture on the flyer showing this alien cavern, a place to walk where there was water only hours before. Either way, it was completely different from anything I’d ever known, and it was a way to forget what I’d lost, the sand and saguaros from home I’d never see again.

I knew I wasn’t like the other men on the crew. They all had that haunted look I’d grown so used to seeing at the refugee center. But I hadn’t lost anyone — except the Earth, which, of course, I felt keenly. Still, my life had been so hollow in the before, empty and silent. I’d had close friends growing up, sure, but they’d all moved away for one thing or another — college, girlfriends, jobs. So, it felt like my life had only really begun in the after, surviving by instinct and assistance while I waited for something new.

And this was new. They were calling it one of the first ‘energy positive’ projects of the rebuilding, set to provide 2 GW a day when it was done, basically returning to the capacity of fossil production in the area in the before. We were finally stepping beyond our own destruction into something new, circular even, like the tides themselves, finally at peace with the rhythms of our world — or so we hoped, anyway.

And I loved every second of it. As the whistle blew to signal the start of the shift, I crouched down, beginning my slow march across the bed of the bay, inspecting another hundred yards of cable. The foremen liked to call my crew the ‘sea urchins,’ laughing at the spikes of tools on our backs as we edged along the lines, but the work suited me just fine. I always tried to go slowly, letting my mind empty as I divided the minutes of my shift as evenly as I could — what I estimated to be a required pace of a yard every two minutes.

I started with the first section, making sure the joints were tight and the casing had no rips before feeling each segment of the cable. Up ahead, I could see one of the skilled crews — engineers, technicians, welders — working on a tidal turbine. It was like a spaceship, the turbines lifting like thrusters from the metal body where it was attached to the sea floor. Unlike me, they worked urgently, forced to finish an entire turbine during each shift before the tides came rolling back in.

Their job certainly had more drama — and glory, presumably — but I liked to think my work was just as vital. Sea urchin or not, most jobs weren’t glamorous, but if no one did them, things fell apart. In the before, people seemed to think there was something shameful about that, as if the pyramid was meant to be inverted. But now, after things had fallen apart, I think we could see that more clearly. Because for a time, everything had stopped, and anyone still willing to do a vital job had probably saved a life by doing it. Maybe ‘normal’ was a thing of the past, but everyone doing their jobs together was probably the closest we’d ever get.

I let my mind go blank, letting the tide of routine sweep into my mind. It was so freeing to have a task I could do without question. I’d been fairly young when things started to fall apart, in the first year at my office job, but all I remember is a sort of dread. Every project felt like a performance review, a chance to either “brand yourself” or be destroyed by another cycle of Machiavellian corporate restructuring. And in the end, after all the scheming we’d all done, none of us had made it. One day, they’d told us all to go, handing us orange boxes with smiling cats on them, stuffed to the gills with branded cups and hats.

“We’ll see you soon!” they’d said cheerfully, locking the doors behind us. I never went back, though. No one did.

Here, in the Bay of Fundy, though, I finally felt some measure of satisfaction with my work. We did two shifts a day, one around seven in the morning and the other around seven at night, taking advantage of both low tides. We finished around ten when the water came back, and the company fed us in a giant tent. It was…fantastic. I wasn’t so naive as to think life would always be this easy, but for now, in the rebuilding, everything was a scramble. Even the supervisors did something on every crew, and there were no performance reviews. One day, the work would be done, so there was no need to fire us ahead of time for quarterly profits. You either laid the cable or you didn’t. That was it.

Near the end of my shift, with ten yards to go and the sun low in the sky, I finally found a snag in the line. I felt it before I saw it, a dent in the plating of the cable. The cables were coated with six or seven layers: polyethylene, Kevlar, banded stainless steel, all of it designed to avoid being pulled apart by the currents. But sometimes, a perfectly shaped rock might get dragged across the sea floor, where it would fly through the cable trench and dent the line. It would take a lot to sever the line, of course, and one day, when the budget ran out, perhaps they would simply run the turbines until they gave out. But for now, they wanted — needed — this thing to work.

“Line!” I called out, waving a red flag over my head. A spotter up ahead waved his back at me, whistling for an engineer to head my way. One of the engineers I knew well eventually made his way to me, lugging a huge bag of tools on his shoulder. I pointed out the spot to him before getting back to my inspections, not wanting to outstay my usefulness — which, despite my satisfaction with the work, was limited.

It still amazed me we could run electricity from the sea floor into Halifax. Even with all the advancements we’d made over the last two hundred years, it was too much for my non-engineering mind to fathom, I guess. Someone had told me that the first transatlantic cable had only been able to transmit forty words a minute. But that at least had a kind of intuitive analog to it. You hit the button on the telegraph and the electricity runs sort of slowly — by modern standards, anyway — to the other side. It wasn’t the lightning-fast stuff we were building here, with electrons running its length in an eye blink. And yet, here I was, just another peg in the process of humanity.

“Good spotting,” the engineer finally said, nodding at me. “That was deeper than it looked.”

I turned, looking at where he’d put in a patch, making the outside of the cable smooth again before it could buckle or breach.

“I don’t know if I’m good luck or bad,” I said. “That’s my fifth this week.”

“Well, in my line of work, bad things always happen. The luck is catching ‘em. Besides, it’s a hell of a lot of water we’re dealing with.”

“True enough,” I said, nodding as he left.

Soon, I finished the line, and the whistle blew to signal the tide had returned to the point where we had to ship out. Luckily, the skilled crew had finished nearby, the engineers hastily wrapping up their test spins on the turbine rotors. Soon, we’d be back at dinner, the energy from that rotor filling the peninsula with light.

I turned to go, pulling my tools over my shoulder. The other crews would take a bit longer — the water sometimes nipping at their heels — but I didn’t mind climbing out alone. Sea urchin or not, it still felt like I was part of something. Like the forest above, you needed creatures who climbed up trees and others who ate dead logs. But for once, I knew what I was, what purpose I served, and I was proud of it.

About this story

Science vs Sci-fi

I can’t help but wonder at the powerful forces that already exist in our world. Each day, the tides go in and out, and a massive flaming ball of fusion energy sits in the sky, showering us with billions of years’ worth of light. Isn’t it incredible that energy just exists around us? After a century of thinking of energy as something purely extractionary — pull it out of the ground and light it on fire — isn’t it powerful to think of taking the kinetic, static, and thermal energies around us and making them into something new?

That’s why this story takes place in the Bay of Fundy. Those tides are real, and they fill me with awe. The land appears and disappears within a single day, sliding beneath the waves only to emerge again. There is also work happening in many places to capture the power of tides. The energy is right there, we just have to dip our propellers in and ride the wave.

How can we change?

A lot of characters in these stories talk about their memories of the work they used to do — some with regret, and others with bafflement at how they used to spend their time. I suppose it reflects a lot of what I — and others around me — seem to be going through. In our modern, specialized economy, work has gotten narrower. While there are still vital, hands-on jobs taking place every day, office work especially seems almost divorced from human reality. We toil away at jobs that do something to support the modern economy, though it’s hard to say what. While some of this work can still be incredibly important — shout out to the millions of people who make it possible for me to somehow get food, write, watch TV, and stay alive in general — sometimes we just seem to be spinning our wheels while also feeling an ever-present dread about deadlines, work-life balance, and layoffs.

While I appreciate the technology and efficiency of capitalism, I think we’ve gone too far in favor of corporatism, short-termism, and inequality. We have to do something about pay that’s been stagnant since the 70s, healthcare, and the myriad other pressures people face. If we took the pressure off, even just a little, wouldn’t we all have time to move a little slower? To stop the race that mows down forests in the name of progress? We can hope.

Further Reading

- Watch the tides go in and out in the Bay of Fundy (and listen to some epic jams)

- Read about the importance of changing work culture socially. Could we even — gasp — implement the four-day week?

Permanent Winter

“Permanent winter?” she asked from the seat next to me, clearly horrified. It honestly took me by surprise. I’d forgotten what it was like growing up in the Midwest, where everyone acted like they were allergic to winter. Personally, I’d always longed for it — with the exception of three o’clock sunsets, I suppose — my body far more suited to the cold. Being hot was a curse, an inescapable pain, and one we’d spent the last two centuries trying to make permanent. But I guess with the warming of winter over the years, people had stopped complaining. Or perhaps they just felt lucky to be alive… Either way, this was a reminder: we were going back to better times, when weather was something you could complain about casually again.

“Yeah,” I said, chuckling, “it’s not for everybody. But I love it.”

“One winter’s enough for me,” she said, shaking her head as she went back to her book. “And Perth doesn’t even get that cold. But good on you; somebody’s gotta do it.”

We were in a solar eVTOL, the plane’s blades whirring through the windows. I’d come over to Australia on an airship, but the company was running these planes for the last leg of the trip, the eVTOL more efficient for the shorter range. Below us, the outback stretched into forever, the baked soil red and desolate. We’d be in Perth soon, but I wanted one more look out the window, anything to clear my head before another full day of work.

Not that I disliked my job. If anything, I was grateful. Most importantly, it gave me a chance to switch hemispheres every six months — accessing the ‘permanent winter’ my plane companion had been so skeptical of. But this was going to be one of my biggest jobs yet, and it would likely take the entire season, perhaps until summer threatened me once more. I was in Perth to fix a single substation, but I’d stay in the country afterwards, installing another twenty.

Through the window, I could see the blades turning upward as the pilots prepared for the approach. By the time we reached the landing zone, they were completely upright, allowing the plane to make its vertical landing. There was a light rain as we touched down on a perfect circle in the grass, the eVTOL pads like crop circles as they dotted the outside of the airport. I could see the terminal in the distance, though it was hard to make out through the airship strips where the grass was allowed to grow wild.

“Remember when airports were all concrete?” I asked the woman as we waited to deplane. She was younger than me, but by the way she frowned, looking out the window, she must have been too young to remember.

“I don’t think so,” she said, smiling apologetically. She’d spoken to me first, asking me to help her get her bag into the bin, but I still hoped I wasn’t becoming the kind of old man who forced his stories on everyone. “By the time I was in middle school, the airports were shuttered, and by the time I was flying, they had airships and biozones.”

“Makes sense,” I said, stepping into the aisle where I pulled her bag back down. “You didn’t miss much; these are better.”

I found my driver near baggage claim, a low-slung hat on his head and a sign with my company’s logo.

“Noah,” he said, shaking my hand.

He led me back to his truck, making an attempt to ask me how the flight was even as he sped ahead, my ears just barely catching each word he tossed over his shoulder.

“This is her,” he said, throwing my luggage unceremoniously in the back. Not that I kept anything important in there… To my surprise, smooth jazz started blasting the moment the car was on. My dad had listened to smooth jazz back in the day. I couldn’t relate at the time, never understanding why he didn’t listen to songs with lyrics. Though, I suppose I was younger then, before work gave me my own stress complex, skyrocketing my interest in wordless melodies.

From the airport, we turned away from the city, heading toward the hills and Mundaring. The city was already doing well enough on their adaptation projects, and I was being brought in to help reclaim the suburbs.

“I reckon you’re the only bloke this side of the planet who can fix a heat pump substation this size, eh?”

“Hardly,” I said. “Just the only one at my company willing to travel.”

“Now that’s a concept. Must be nice.”

I smiled, going back to looking out the window. I was getting older, but it’s not like there were pensions anymore. So, until we fixed things, I’d stay on the road, avoiding the heat as best I could.

As we left the airport, heading east on Koongamia, the fields outside the window were suddenly completely white. Like the sails to some kind of massive ship, shade cloths covered the landscape, climbing the hills as they reflected the sun back into space.

“Quite a sight, eh?” Noah asked, following my gaze.

“It is,” I mumbled, still mesmerized. I shook my head, turning away. “I’d heard, but… I guess everyone’s mitigation is different.”

“Suppose so,” Noah said. “Sure saved lives on the bad days.”

We rode the rest of the way in silence, until we were well into the hills. Suddenly, the traffic on the Great Eastern Highway slowed, pulling into a sort of roadside checkpoint, where armed guards were inspecting the cars. Noah flashed a badge, and we were waved right through, turning off the highway and into town.

“Is it restricted up here?” I asked, looking back at the checkpoint through the truck’s rear window.

“Well, we’re trying to keep the right people in here. Won’t be long before we’re off credits, after all.”

“Oh,” I said, slumping back into my seat.

It’s not like I’d never seen corruption before. In the darkest times, there was hoarding and bribery. But there were coups and assassinations too, and it felt like we’d finally reached a sort of equilibrium, everyone pulling in the same direction. After five decades of misinformation and science denial, there was finally evidence in front of your face that we needed to work together. And for the most part — minus a few millenarian movements — people had.

But I guess good things don’t last forever. Like the post-war period a century ago, we were switching from guns to butter, and not everybody was going to get a slice. Still, it made me horribly sad. The only silver lining to the collapse — for me, anyway — was that I’d thought we would once and for all free ourselves of the golden handcuffs. It was a shame people were so easy to put them back on. But I guess even if you walled off a town, you couldn’t deny the truth: we need each other. Even these new suburbs were going to rely on advanced cooling — at least until we all got back below two degrees — and you simply couldn’t do that without a society willing to back you up.

At the first big clump of buildings, we pulled off the road, following a dirt track through the bush until we came to a massive concrete structure dug into the hillside. Built into the shape of a giant hourglass, I could hear the whir of the blades even before the truck stopped. This was the second largest heat pump substation my company had, and I’d honestly always wanted to see it. The sheer audacity of pumping cold air into some five thousand homes seemed like just the kind of thing we ought to be doing after everything we’d been through.

“Tools inside?” I asked, opening the door as soon as we stopped.

“Sure are,” Noah said. “Guess you’ll let me know what you need?”

“I will,” I said, closing the door behind me.

For the next few hours, it would be just me and the machine. I stepped through a porthole in the concrete tube and onto a metal platform. The lead fan was still spinning, but the report said capacity had dropped 10% and no one knew why. Unfortunately — or fortunately for an aestophobic repairman — the substation had hundreds of parts. It was like the heat pump behind your house, only, well…the size of your house. And that meant the compressors, evaporators, and condensers all had a dozen units put together and operating in tandem. A single fuse could have blown, taking out a tenth of the units. Frankly, anything could have happened.

I got to work, plugging in my diagnostic reader as I paced around the walkway, looking for obvious wear and tear. But as I did so, I couldn’t help but let out a sad laugh. I still couldn’t believe they were trying to start some kind of exclusive community up here. Having built this incredibly complex machine, one that took hundreds of workers and generations of expertise, they wanted to choke off access to it. As if our situation weren’t riding on a razor’s edge, they wanted to introduce fresh scarcity — and bring back the old god: profit. But hadn’t they learned anything? Thatcher had lied. There was a different way to live, there was an alternative. We’d lived it, scraping life from the bones of our fallen friends.

Maybe I was just starting to wax poetic in my old age, but I couldn’t help but feel the metaphor in this machine. Humans were exactly the same, taking hundreds of parts to make us go, to allow life to cling to the planet. But you didn’t see the fan telling the fuse box she was lesser. You didn’t see the coolant trying to raise rents on the inverters. I knew I was just another part, but I was proud of that. I was here because someone else had kept me alive. And my work here today would probably save another life still.

I heard a beep from the diagnostics. I took a deep breath, squaring my shoulders as I walked back to the panel. I couldn’t change the human condition. Hell, I could barely even manage to stay in one place. But today, I could fix this machine. I could keep these houses cold. And once I did…maybe they’d listen to me about who should live in them.

About this story

Science vs Sci-fi

First, let me state for the record that I’m a big fan of winter. It makes me a philistine, I know, but it is certainly not science fiction that your favorite neighborhood author is a sweaty mess all through the summer. So, a character that chases the sweet bliss of brisk days and sweaters? Sign me up! Unfortunately, that also means the world is all but certain to be climactically not to my liking. Not that I’m a proponent of an Ice Age — yet…

As for the technology, there’s three main buckets worth mentioning:

1. Heat Pumps

These are, of course, very real, and you can get one! They’re wicked efficient, and basically they work by putting air conditioning in reverse, using a smaller amount of energy to put either hot or cold air from the outside into a condenser and moving it around your house. I have one behind my house, and with the newer high-efficiency models with inverters it helps heat my house — even in snowy Chicago — until it’s basically a polar vortex. Even better, if you live in the United States, heat pumps are one of the technologies you might be able to get benefits for through the Inflation Reduction Act. The science fiction, of course, is about scale. In this story, our character is working on a giant heat pump, one that can supply hundreds of homes.

2. Planes

One of the most satisfying parts of writing this piece was imagining what an airport of the future could look like. Even as flying has become commonplace, it’s always held a certain fascination for humankind — if not for technological reasons in our day and age than at least for the sheer possibility of being able to go anywhere we’ve dreamt of.

However, flying is also complicated for everyday folks since it’s a big portion of our carbon footprints. Unfortunately, in the US, without the focus on building out reliable train transport, it also can feel like the only way to see our loved ones. Offsets could be part of the equation — though the offsets we have now are often of dubious quality. So there still seems to be room to improve how we fly.

One problem, of course, is that it takes a lot of energy to get a plane off the ground. The eVTOLs (electric vertical take-off and landing vehicles) featured in this piece are real and being scaled up as we speak. However, since they’re electric, part of the challenge will be to solve for long-haul flights, where the weight of current batteries will make it harder to have electric planes fly long distances. Part of that could involve using what the industry calls SAF (sustainable aviation fuel) — making jet fuel from more sustainable sources like agricultural waste — or possibly trying to scale up hydrogen to a practical stage for aviation usage. SAF may only be a matter of time and scale — though industry goals are still far off — but this one might be more sci-fi for now. In the piece, I describe only the use of an “airship” to reach Australia, but maybe someday, we’ll fly in just that.

3. Big Ole White Tents

Part of the beauty of including “technology” like this is that it’s right at our fingertips. We’ll talk a bit more about surfaces in another section further on, but as we think about climate mitigation, it’s important to remember that technology is a resource challenge, and sometimes doing something simple is better than doing nothing at all.

How can we change?

One question you might be asking yourself is why this matters. You may be perfectly happy with your gas furnace, thank you very much. The essential idea, however, is to “Electrify Everything.” Even if electricity isn’t 100% renewable yet, we’re working to get there. However, once we have all that clean electricity, we’re going to need to be able to use it everywhere we currently use fossil fuels if we want to fully transition our energy mix.

The great thing about the home — if you’re lucky enough to own one, which I know is sadly out of reach for too many — is that you get to call the shots. You have to pay that dreaded mortgage and replace all those appliances when they break, of course, but until then, you get to look out your window, smiling at your beautiful heat pump! (I do this, and my neighbors do indeed think it’s weird. Sorry Apartment 2B…)

This might take some time, of course, and there’s nothing wrong with that. For budgetary reasons, I’ve decided to attempt one major project each year on my electrification journey. For you, that might be less or more, but the point is to take that first simple step. With my heat pump and an electric griddle instead of my stove, I reduced my gas usage by 75%. It’s easy to feel powerless against something huge like climate change, but a single step from each of us can turn into miles.

Further Reading

- Watch this video about how heat pumps work — and, you know, nerd out about it if you want to

- If you’re like me and live in a cold climate — and want to have sweet arguments for the skeptical HVAC guy in your neighborhood — check out this guide to cold weather heat pumps

- Watch this video to experience what an eVTOL is like, and this video if you just wanna have a good cry

A Sort of Parent

Alloparenting.

The word finally came to me. It had been years since I’d thought of it — of anything that technical, I suppose. I think before everything fell apart, it had given me hope, a sort of path forward for humanity. We had to live with less: fewer children, fewer houses, fewer things. Someone probably had to have kids — replacement rate and all that, not to mention all those deaths — but what about the rest of us? Living the same isolated, individual-obsessed lives we’d had before clearly wasn’t going to work. But if we connected, being a part of one big life all together, perhaps we could solve for some of the cracks in the way we lived.

Now, it’s just what we call parenting, I guess. If you were lucky enough to still have loved ones left alive — and I mean the ones you chose — it had just become the way things were. You lived together, ate together, somebody taught the kids how to read. But I found myself searching for a term again, searching for something to validate what I had become. Most of the kids in the house called me Uncle, but what was an uncle anyway? Somedays, I felt like I’d entered a non-place, where I didn’t recognize myself and no one else did either.

“Why’d you pick me up anyway? Where’s my mom?”

“Your mom…” I started to answer before I stopped myself. I shot a look back at Lill. That was a hell of a tone to take with an adult. Still, she was unfazed, cocking an eyebrow at me before she went back to whacking the bushes with a stick. We were on the path back to the house, taking the shortcut through the woods. Fourteen or not, she was the smartest of the kids, and she knew she had my number. ‘What the hell are you gonna do about it?’ that look seemed to say.

“She got called to the dam,” I continued, relenting. “Something about a broken rotor.”

Lill muttered something under her breath.

“Don’t turn this around on me,” I continued, forcing myself to find the stomach to confront a surly teen. “You’re the one whogot in a fight. Why’d you hit that girl?”

She mumbled something to herself, which sounded like it included some choice swear words, though I decided to let that slide, basically a sailor myself. I stopped, turning to face her on the path as I folded my arms — as if that would somehow protect me from her sharp tongue.

“Come on, Lill, I can’t help you if I don’t know. And you know I got these old man ears. Just tellme what happened.”

She almost smiled. She loved making fun of my ears — affectionately, of course. I’d worked on the rescue boats too long, and I could barely hear anything after being next to the engine all those years. Still, almost smiling was hardly the real thing, and her jaw bulged, clearly grinding her teeth.

“Fine,” she said, rolling her eyes as she walked ahead of me on the path. Still, when she spoke, she at least did so loud enough for me to hear.

“They all think I’m weird. They all live in the row houses — the little pampered airheads — and I’m stuck on the farm with who knows how many parents. They always look down on me, but today, they started following me down the hallway, making a buzzing sound. Buzz, buzz, buzz. So I snapped. Still, I’m not sorry. They can kick me out for all I care. I should be working anyway; mom always says so.”

Her mom most certainly did not always say so, but I held my tongue. There was no way to insert yourself into the thousands of wounds generated between a mother and daughter. All you could do was try to love them both. Besides, it must be hard. I’d been bullied too — a thousand years ago — and while there were plenty of other families like ours dotting the hills, she was the only one at her school. We were the closest to town, which meant the other families all had jobs at the depot, with single family housing to match.

“I’m sorry,” I finally said when she finished. “We’ll figure something out together.”

She shot me a look over her shoulder. Together might sound like a threat, but I meant it in a good way. I’d go to bat for her, find a way to deal with those horrible kids without embarrassing her further. I just had to hope she’d get all that context as I used as few words as possible to keep from scaring her off.

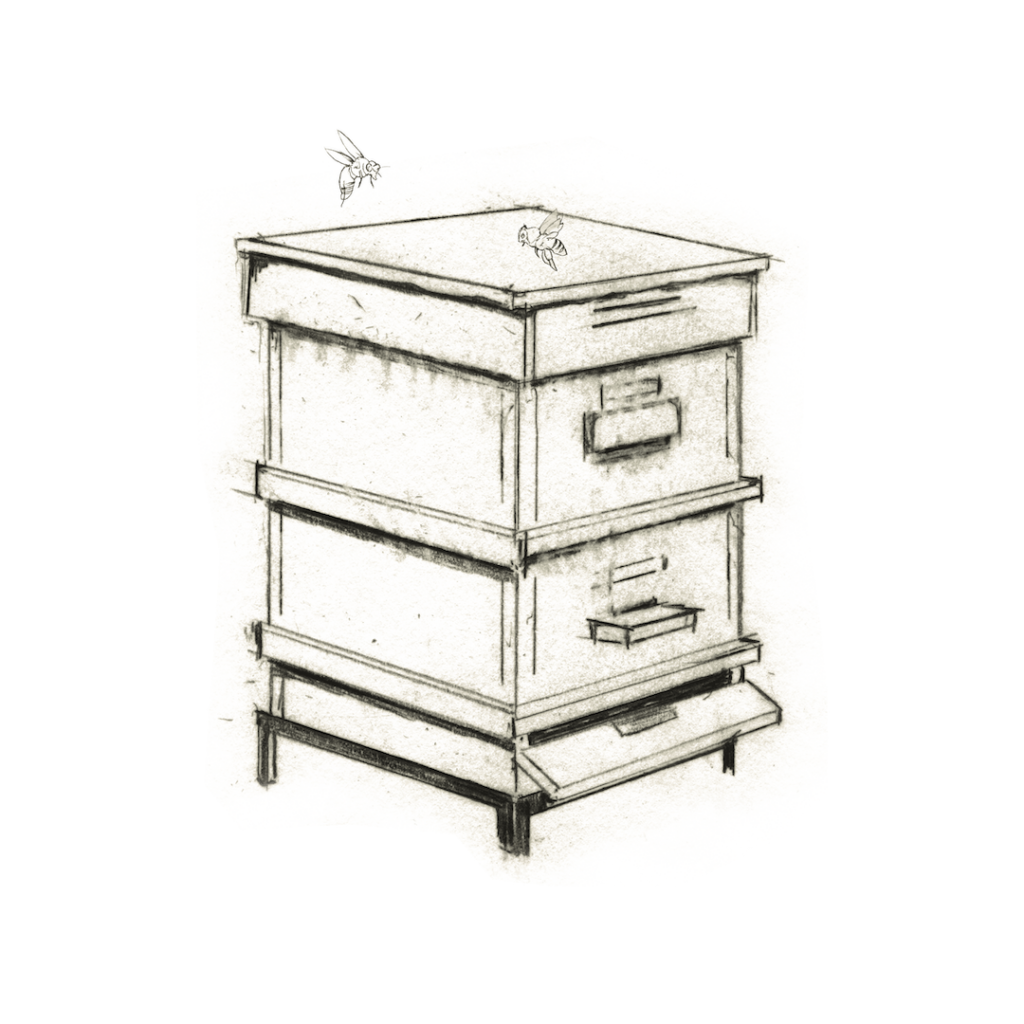

We reached the end of the woods, the sound of the Illinois River passing through the trees. On the left, our giant field opened up, the hundreds of hives like buzzing statues as the bees wandered the fields in search of pollen. Beyond that, on the hill, our house poked its head over the trees, a handful of the lights on as the other aunts and uncles busied about the house.

“I have to stop to check on one of the hives,” I said, turning back to Lill. “You can stay with me or go up to the house, but I can’t promise you won’t get a talking to up there.”

She looked up at the house, weighing her odds.

“I’ll stay with you,” she said with a sigh.

“Thought so.”

She could give me a bad rap if she wanted to, but she knew I was the easy one. Even if it meant I had no spine, it still gave me a sort of satisfaction. If she turned out alright as an adult — which didn’t seem like a stretch, knocking that girl’s teeth out notwithstanding — it might give me a shot at being her favorite uncle. And if she didn’t turn out… Well, the others had certainly done their best.

We turned into the hives, the giant triangles giving off shade from the afternoon sun. Even after all this time, I still liked to look at them, the federal models like some kind of spaceship in my own back yard. They looked even more surreal when it flooded, the hives rising on their poles as they floated out of harm’s way.

“Why do we have to do this?” Lill asked, still swatting her stick through the air — which made me pray she didn’t accidentally hit a bee. They were all used to our scent, of course, but they wouldn’t — and shouldn’t — take kindly to being smacked by a teen.

“This was the deal when the government gave us the deed to this place. We do something with the floodplain, they give us a house. It sure as hell beats a mortgage.”

“What’s a mortgage?” she asked, the curiosity actually entering her voice again, the tone I’d grown to miss as she left childhood behind. It wasn’t totally impossible to resurrect — she’d been obsessed with the past when she was younger — but it still struck me as a breath of fresh air after so many months of teenage angst. Not that I was any better at her age…

“It’s the way we used to get houses. You’d borrow the money from a bank and take like thirty years to pay it back. I guess it wasn’t a bad deal, but it was kind of like a prison sentence too. Kept me in an office job I hated, kept your mom working at the oil company.”

“When she wanted to be a water engineer?”

“I don’t know,” I said, continuing down the row of hives. “I don’t know that it was water necessarily, but I think she wanted to be any other kind of engineer, one that wasn’t hurting people.”

Lill was quiet after that. Sometimes she liked to use her mom’s work in the oil fields as a kind of weapon, a wedge to give her the moral superiority teens so crave. Even if she didn’t totally know what oil was — thank heavens for that — she knew it made her mother feel impossibly guilty. But now… She seemed to take the information whole, part of the fabric of her parents’ identities.

We finally reached the end of the row, the bucket I’d been filling with honey still waiting where I’d left it when I ran off to the school. Lill flopped down in the shade, and I let her. Sometimes, it helped to do an activity together, but not today. I popped the lid on the hive, working quietly while she stared at the sky. After a while, though, she groaned, burying her head in her knees.

“I hate this place,” she said, her voice muffled. “I just wanna run away.”

I stopped, wiping my brow as I forced myself to suck in a deep breath. I stayed by the hive but turned, squatting down to her level.

“I get that,” I said.

“No, you don’t,” she said quietly. “You love it here.”

“Sure,” I said, “but this is something I chose, and you didn’t get to. Besides, I was the same when I was a teen. You’re supposed to hate the box we put you in. That’s how society changes, it’s just…”

I paused, looking around at the hives. They looked so impossibly beautiful to me, like nothing else I’d ever seen. Suddenly, I felt one of those rare waves of honesty surging up. One she could use against me later, but one she deserved all the same.

“Before, I hated my life, too. I spent all my time wishing I was free, wishing things were different. But I never did anything about it. I think I was afraid of living. We all were back then, at least a little. We had to do everything so…perfectly, just to make sure we didn’t starve to death when we were old. But we starved anyway, and now…I wish I’d done things differently.”

Lill lifted her head, meeting my eyes for just a second before she looked away, staring back at the sky.

“What do you wish you’d done differently?” she asked quietly.

“Well,” I said, sighing as an old face came back into my mind, “there was a woman, an artist. We dated for a while, and I loved her, I think, but I never gave us a chance. She was too free, too chaotic, and I didn’t think it would work out. But knowing what I know now, knowing that nothing worked out… I guess I just wish I’d spent more time with her. Or maybe I just wish she and I could have jumped to right here, to this field, to these bees. I have everything I ever wanted now except for her.”

Lill looked up at me, considering me anew as I smiled awkwardly, the embarrassment catching up with me. What was my point? Did I even have one? Was I breaking the adult fourth wall or just spouting off more useless advice?

“What was her name?” she asked.

“Lisa,” I said, just above a whisper, like the name was a spell I didn’t dare utter. Still, this was about Lill, not me, and I pushed ahead, desperate to use her brief window of attention to help her somehow.

“Look, when you finish school, you can do whatever you want. You can leave, even. I’d support you, help you explain to your mom and whatever else. Just…don’t put yourself in a box. Don’t do what I did, convincing yourself there’s only one way you can be. Even if you run away — even if that’s the total opposite of me living a safe, meaningless life before — it would still be a box. One day, your mom will get off your case, and those kids who give you trouble at school will learn to at least pretend they aren’t little shits. You can go, but if you want to, you can stay. Just be who you really are, and the rest will sort itself out.”

She took a deep breath, looking toward the river, but when she looked back, she actually smiled.

“I guess that’s actually kind of good advice.”

“It is?”

“Maybe, but don’t tell anybody.”

She stood, taking my honey bucket and slinging it over her shoulder as she headed toward the house. I chuckled, putting the cover back on the hive, the bees buzzing happily around my head. Maybe I really was a parent. An alloparent. Still, I was something, and that felt a whole lot better than anything I’d ever been before.

About this story

Science vs Sci-fi

We’ve got a lot of people on this planet, there’s no question about that. While humans are the cause of climate change, humanity is also part of what makes the world beautiful — I certainly couldn’t be a writer if I didn’t think so, even if humans make the world hard and scary sometimes. Humans are complex, of course, but that’s sort of the point. We don’t live in an ‘either-or’ world (where the world/humans/society are either good or bad). We live in a ‘both-and’ world. I think we need to preserve the planet not in spite of ourselves, but as a part of ourselves. We’re bound up with nature, and the whole point of climate positivity is to focus on how we can become part of the solution. We invented this mess, but by changing ourselves, we can help ensure something beautiful comes out the other side.

So, should you have kids even as climate change threatens? I’d say that’s up to you. Grist has a great piece on the topic that I think sums up some of the issues nicely. But as the author notes, children can motivate us to do more for the climate. Those children could also help invent new solutions. We might be bringing them into a world of suffering, but that’s sort of always the case with life.

How can we change?

The conversation about having children aside, I wanted to explore a different model in this piece, too. People are having fewer kids, and hard times may make them have even less. Still, the kids that we do bring into this world deserve a chance at love and life. That’s part of why I’m so interested in this concept of alloparenting. I don’t plan of having kids of my own, but I already love the kids my friends have had, and I think they deserve to have lots of loving people in their lives — even the slightly weird, mediocre-writer uncles. I think parents deserve that help too. We may have hard times and challenges ahead, but we have beautiful times left too. And if we do it all together, it will be that much more beautiful.

Further Reading

- Watch this TED Talk from Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, a scientist and a leader in how to find joy in fighting climate change

- Johnson also worked on the All We Can Save Project, which, in part, looks at the importance of community in the climate crisis

- Already have kiddos in your life? Check out this guide to talking about climate change

Towers

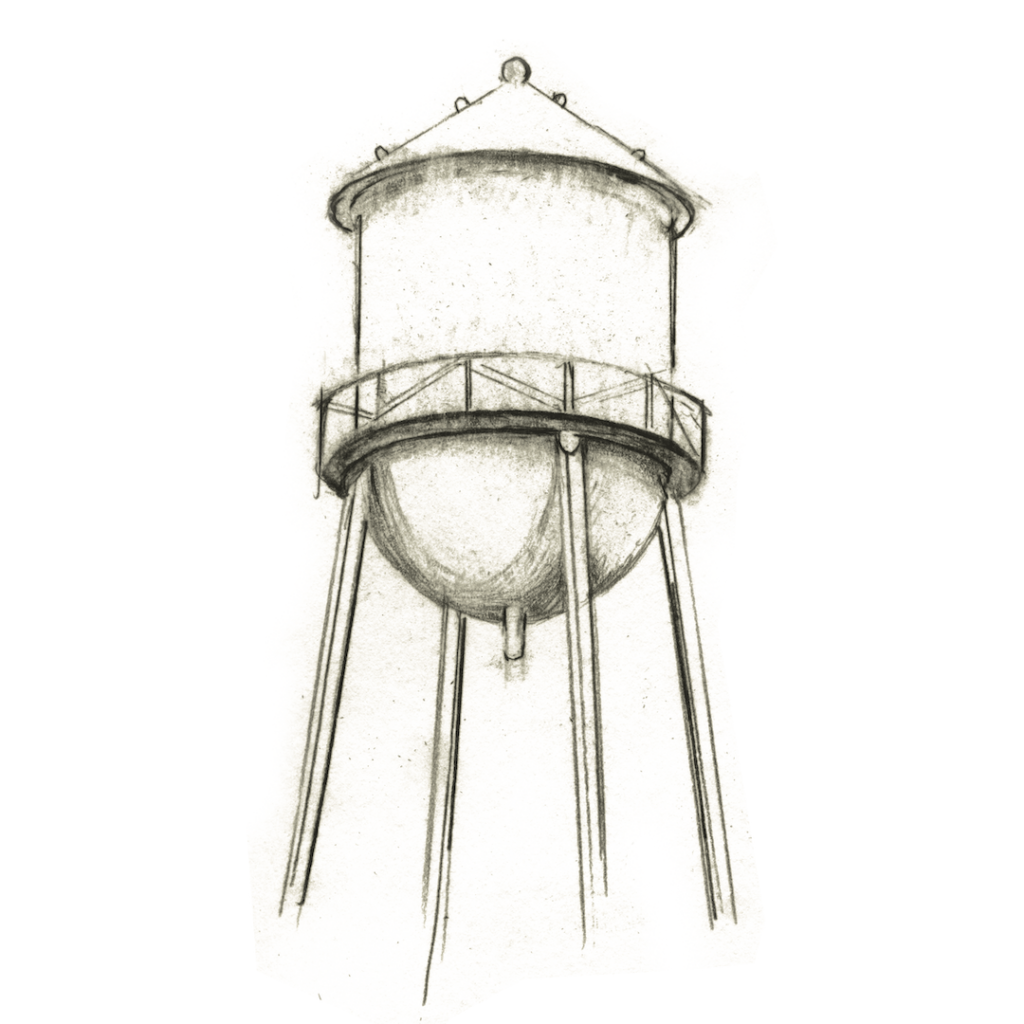

I looked down into the water tower, just catching the shine of the water in the darkness. It was still about half-filled, but it was going to be another hot week, and the people who lived below would surely appreciate the extra water for their gardens. I leaned over the edge of the roof where my team was waiting below.

“Alright!” I called down. “Fire her up!”

They started working the pump, pushing water from the wagon up to the third floor. After triple-checking the hose connection, I turned, looking across the roofs where another dozen water towers sat waiting in a near-perfect row. This was my favorite street, one of the only places in the city where the houses were close enough in size for all the towers to line up like this. Still, no two were alike, most of the owners having painted their own little murals on the aluminum siding.

My daughter and I had painted the one on our house, too, even if our street was less…participatory. She was only five, but she’d still drawn me with a hose in my hand.

“Mommy does the water,” she’d said.

It made my heart swell with pride just thinking about it, though maybe it was to be expected with how obvious I was about my love for this job — hell, I’d even gotten a tattoo of a water tower on my arm, the old kind from the 1800s with the metal ridges. But it felt fitting. Even with the new aluminum models, I felt like a time traveler, bringing back everything we’d lost one gallon of water at a time. And if that let me live in the present, if it let me have a daughter — and the confidence I’d actually live to see her grow up — I’d wear my silly tattoo proudly.

It wasn’t like I didn’t have nightmares — everyone still seemed to — but they didn’t linger like they used to. In fact, when I wake up now, I can hardly remember my dreams at all. Maybe it’s some sort of trauma response. Like my own mother and the way she used to talk about COVID. She called it a time warp, a narrow funnel that wiped your memories away. I was too small to remember, but she’d always said it had changed me too: the games I played with my toys, the things I talked about.

I guess the mind can only take so much suffering. But forgetting can be healthy, too. What good would it do for me to talk about ‘trophic collapse’ and ‘degenerative heat cycles?’ All I really need is a vague impression of those times and the lesson I learned: we got through them together. All my work on the neighborhood emergency council, the tallies, dividing the supplies. As traumatic as those times had been, they hadn’t been some machismo fantasy either, everyone shooting at each other as they fought over the last chocolate bar. We’d survived by clinging to each other in the storm, and I wasn’t about to let go just because the sun had started shining.

“Rice up!” someone on my crew called.

“Heard,” I called back, coming to the edge where we’d attached the winch, five big bags of rice rising in their metal basket.

Before the rice reached the top, I took one last peek into the water tower, making sure it wasn’t about to overflow.

“Ten more good pumps,” I called down, coming back to the side as the rice reached the top.

Squatting, I pulled up each bag of rice, carrying it to the metal bin next to the water. They were surprisingly similar in weight to my daughter, actually, though whether lifting her was good practice or just more punishment on my muscles remained to be seen. Still, I wouldn’t trade it for anything. Soon, she’d be too big for me to lift, and then she’d even get to be a teenager in a way I never did. Even as it would surely break my heart, I wanted her to have that, refusing hugs and stomping off to her room like I’d only seen in the movies.

Finally, the sound of the water started to change in pitch, the air in the tower running out as it filled. Still, I had no fear of it overflowing now. I trusted my crew, and when I said ten pumps, it would be exactly ten. I looked through the hatch one last time, the rippling water beginning to still. It was so close now, I could see the shimmer of my face in its surface. It was too dark to make out details, but I didn’t need a mirror to know that I was smiling.

About this story

Science vs Sci-fi

I made a point in this piece of calling out prepping culture, though I hope not in a judgmental way. I think we’re all at risk of the allure that prepping provides, that we might somehow do enough to prevent catastrophe in our own lives. But even if you could somehow buy everything you needed to live, how many years could you really make it? Five? Ten? It’s a fantasy. In the end, everything we do requires access to each other. Humans aren’t a monolith. After all, the old village in the song needs a cobbler, a baker, and a candlestick maker. Still, that’s part of what makes humans beautiful, too. We each get just one life. A life where we grow up, fall in love, learn a craft. We become a single strand on a web of each-otherness, coming together to make life as livable as we can.

It makes me think of the scientist Vaclav Smil. In his latest book, he talked about how essential materials science is to society. As a Times review put it, he sees “four pillars of modern civilization: cement, steel, plastics and ammonia.” Ultimately, our ability to act on climate change comes down to an age-old human dilemma — how do we make things? And how do we make them fast enough to make a difference?

How can we change?

I, for one, plan to go down with the ship. I plan to fight the good fight with my other humans as we do our best to make a change — a change that’s entirely possible, with the latest US climate report finding that we have the technology already. But as Vaclav Smil says, we have to focus on building it. Still, instead of prepping for disaster, I urge you to find hope in your humanity. Love your people, create your art, go to your jobs even if they seem pointless some days. Society is something we do together. If you believe George Constanza, of course, society is rules. It has rules, yes, but it’s more than that, too. Society is painting, welding, precision steel. Society is me. Society is you. Let’s do this together.

Further Reading

- Read this article about billionaire preppers trying to “transcend the human condition” for an example of what not to do

- This story takes place in Chicago, of course, but watch this video to learn more about water towers on buildings

- Looking for a bipartisan way to build community and take action on climate change (and put all that nervous prepper energy into something positive)? Check out Citizens’ Climate Lobby

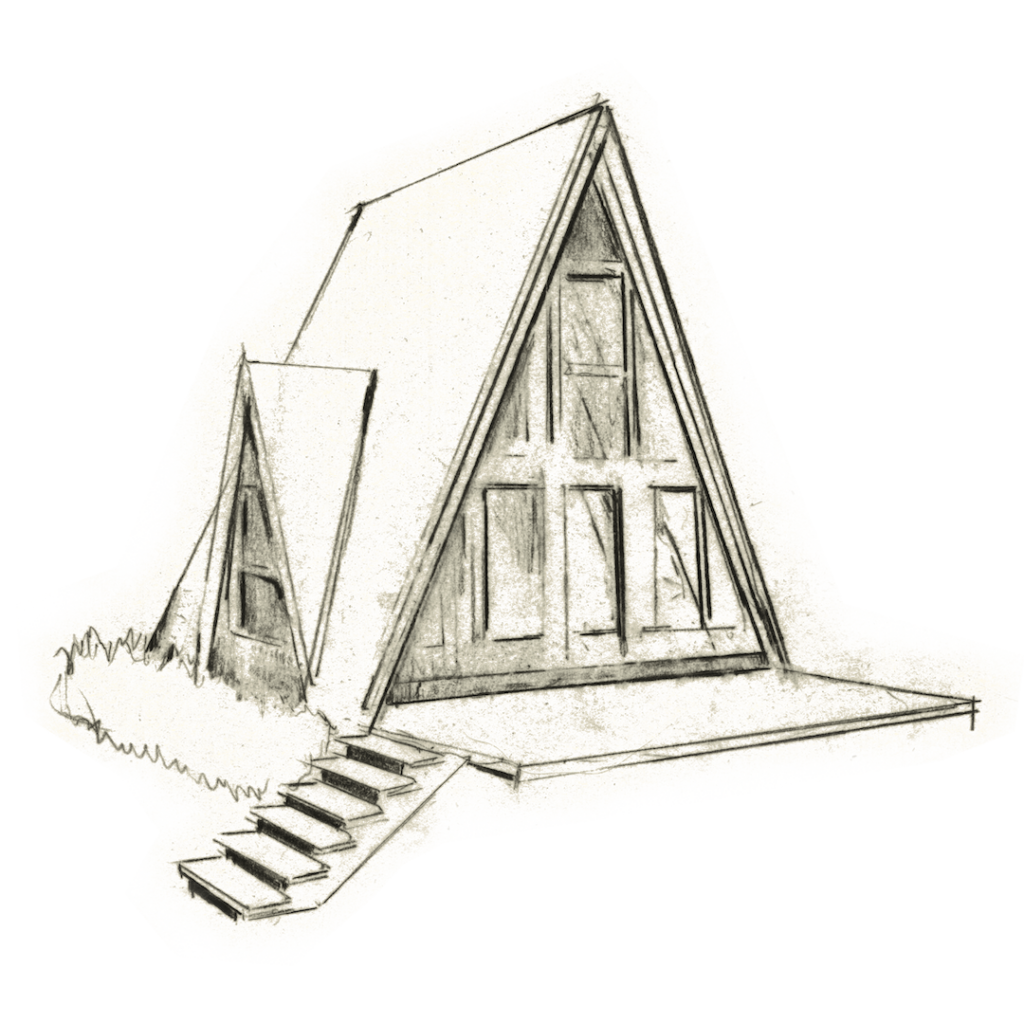

The Cabin

I was at the edge of the world, where life ended and death began. Behind me was my cabin: quaint, rustic — shockingly spared from the destruction — and ahead of me… The earth was scorched, the hills like a graveyard of ancient bones, the charred remains of tree trunks the only thing to interrupt the chalky earth.

They had sent me to find seeds, but it was slow, lonely work. The old pines, which were supposed to grow anew in the wake of a fire, had struggled to survive. The fires had been too close together, and the growing season after them too dry for anything to take root. Now, the government was starting over, trying to plant a new forest in the north, but they needed seeds. And perhaps, if they made someone like me look long enough, I’d find a pinecone or two they could use.

I put my pack on my shoulders and clipped on the hip belt, carefully adjusting the straps until the weight was balanced. Not that anything had changed in my pack… I carried the same kit into the forest each day, the same tools and the same amount of water. But it was a ritual, and one I needed. Maybe it was more of a superstition, like the old pro sports players from before who couldn’t hit the ball without their shoes laced the right way. Either way, it was my own personal prayer to the forest, pleading that if I just showed enough care, proved I was worthy, the trees might offer up their treasure.

I could have used more water, of course, baking in the sun as I wandered the hills, but like everything else, my water was rationed. And for good reason. Many of the aquifers in the area had collapsed from overuse. Unfortunately, aquifers don’t just refill like a jug. They’re carefully constructed by time, pockets deep beneath the earth forced into the structure of the clay. And when they’re emptied out? Boom! Collapsed, no more aquifer. Still, it was a miracle they’d found this one intact. I took my daily allotment with me into the forest — saving just enough to cook my meager rations after my shift — and it was a sort of life, hoping for enough rainfall to keep going but not so much the scarred hills wiped me off the map with a mudslide.

With everything set, I tapped the beam above the door, my ritual complete as I stepped off the porch. My boots crunched their way over a bed of brown pine needles, a sort of moat made of kindling separating my part of the forest from the other. And like every morning, it made me think of Quinn. We’d met in the Tree Corps, and the first time she’d kissed me had been on a bed of needles just like these. We’d taken our lunch under a tree, scooping the needles into a pile.

“It’s our own private sofa,” she’d joked, pulling me down beside her. “It’s funny I can still enjoy things like this. This is another fire waiting to happen, but I can’t help it.”

I hadn’t had anything particularly good to add. She was the clever one in the group, the eloquent one, but I’d smiled at least, and she’d seemed satisfied. It wasn’t a move, my lack of words, but she’d always seemed convinced there were multitudes hiding behind my silence. I did think more thoughts than I said, didn’t I? Maybe it was like scar tissue, covering over the person I’d been before. But would Quinn have liked the old me? Before the worst years, before I’d lost my family, I’d been talkative, hadn’t I? Talkative-ish, anyway. For a while, it had felt like I never stopped talking, always boring someone half to death with my grad school anxieties.

“But if I did this program, then maybe I’d be qualified to—”

“No, I know, but my résumé can’t compete with—”

“If only I hadn’t been a teenager then. Who lets an eighteen-year-old pick a major that defines the rest of their life!”

But I suppose it was only natural to be anxious back then. There were a thousand fires burning in those days — both literal and figurative — growing ever larger on the horizon. Even as I droned away in the lab, desperate to make some kind of use of my botany, there hadn’t been an obvious path. I’d specialized in lichens, and their habitat was evaporating before my eyes. How could I be useful against all that crisis?

In some ways, those voices had quieted after everything was lost. Suddenly, there was always something pressing and vital to do no matter what your skills, our collective descent down the hierarchy of needs suppressing my constant quest for meaning. More importantly, Quinn had given me meaning. Rebuilding the world had given me meaning. But now? Now there were choices to make again, and I felt paralyzed. Even this job hadn’t seemed possible, but Quinn had pressed me to take it.

“I know we’ll be apart for a while, but the way your eyeslit up, I can tell you want it.”

But did I? What about all the other things I could be doing? What about my time with Quinn? They had still barely ramped up antibiotic production. What if I lost her to a cold, something she’d promise was only the sniffles while she volunteered for another night shift? If I wasn’t hiking eighteen miles a day, I’m sure it would have made me sleepless with worry. But that was the problem with every job I’d ever had. Someone had to do it, but should that someone be me?

“If anyone can be in the woods alone for three months, it’s you,” Quinn had said. “No offense. I mean it in an endearing way.”

And she had. She’d touched my arm and everything, making my heart drop into my feet. And she was right. I was good at being alone. Even if my mind was always churning with thoughts. Or maybe that was my secret? It reminded me of someone I’d worked with from before. They were incredibly efficient, perhaps too efficient, and they’d revealed to me one day that they had terrible OCD.

“Well,” they’d said, laughing at my surprise — seeing as my anxious thoughts kept me from doing anything useful. “There’s days I can’t do anything at all, true, but when you grow up learning to multiply alongside your intrusive thoughts, you become a pretty good multitasker.”

I guess we all went where we were suited. And even if I wanted to help with every single problem in the world, in the end, I could only work on one at a time. Besides, for as many useless mes as there were, there were probably a hundred Quinns, and they were getting us closer to something real, something good.

It was good to think and hike, of course, but like usual, I’d walked the first three miles in a trance, only realizing as I reached the top of the first rise. I stopped, putting down my bag to take a drink. I’d started calling this place Hornback Ridge. There were no accurate maps anymore — everything either burnt away or washed down the slope in a mudslide — but I’d gotten to know the area. And in a place this desolate, you had to make your own landmarks. Hornback Ridge was like a dragon’s back, its knobby spine winding through the burnt forest.

I pulled my own makeshift map from my bag, looking at all the areas I could still search. I’d put X’s through about half of them, starting each day at the ridge before fanning out in one direction or another. It was the highest point on my side of the mountains, and it kept me from getting lost.

I started to the west, the hours slipping by as I followed the slope of the hills. For a while, I was still in areas I’d at least scouted before, recognizing random boulders and trees along the way. But something that day pulled me farther. It could have just been the melancholy of thinking about Quinn — something that always made me walk farther than I should — but it just felt right. Even as I pushed toward the edge of my map, knowing I’d have to retrace whatever distance I walked to get back, I just kept going.

I walked all day, until the sun was more than halfway through the sky, when the ridge line just…ended. I stopped, looking down at a valley I’d never seen before. The mountains continued in the distance, but there was a gap about a quarter-mile wide nestled between the hills. I went up to the edge, tempted to reach for my pencil to mark it on the map, but something else caught my eye.

At the bottom of the valley was a giant cave. How had no one mentioned this before? It was angled downward like a drain in some god’s bathtub, the eroding valley swirling toward it. More importantly, the soil was much darker. From the top of the ridge, I could see the change in color clearly. It was retaining moisture somehow, a miracle in its own right.

I started down the valley, forced to walk sideways so I could shuffle down the steep slope. But even as I worried I’d break my neck, I couldn’t stop looking at that cave. I was tempted to slide my way down, but out here alone, a twisted ankle would end me just as easily as a mudslide. Still, before long, I reached the bottom, the soil seeming bouncy after so many months walking on ground as dry as bone. I stooped down, rolling some of it across my hand. I giggled like a kid, suddenly tempted to make a mud pie.

As I looked up, I locked eyes with the cave, the massive chasm drawing me in. The opening was some thirty feet wide, the rock just…torn away as the cavern disappeared into an inky blackness. I began walking toward it, uncaring for my lack of flashlights — I’d only go in a few yards, right? — when I stopped. There, on the ground, sprouting from the field of dark soil was a sapling. And surrounding it, pulled from the valley by the power of the drain, were hundreds of pinecones.

I fell to a seat, staring at the little tree. I’d found it. Or maybe, it had found me… Nature had found a way to answer the impossible question we’d posed to it: Can life push through the terrible things we’ve wrought? Apparently, it could.

“Thank you,” I said, looking at the cave. “We don’t deserve it, but thank you.”

About this story

Science vs Sci-fi

All of these stories aim to be about more than tech, delving into the human experience of climate change. Still, this was one without a specific technology in mind, so as I started to think about what I wanted to write for this section, I was reminded of COVID and the way animals reclaimed cities during lockdown. This piece focuses on trees, but the question remains — can nature heal itself?

First, I think it’s important to define what ‘healing’ means. The planet will almost certainly always exist. It’s been through millions of years of change. The problem is, some of those changes nearly wiped out all life on the planet, and a vanishingly small portion of Earth’s history involved humans. Even if all the humans die, Earth will likely get a do-over. The more important question is whether or not the world will heal in a way that looks familiar to us, in a way that sustains and grows life with food, shelter, and bearable temperatures.

Second, as I mentioned earlier, I think it’s vitally important to remain positive about climate change. Doom only breeds a freeze response and does little to change the threats we’re facing. There’s certainly a risk that we wait too long — climate change can cause cascades that form feedback loops. Examples include: the melting permafrost, which can release more carbon into the air, and melting polar ice, which can disrupt ocean currents that move heat around the globe. Still, I’d like to think that with enough suffering, the political will we’ve been avoiding would materialize quickly. After all, in these stories, humans are still around. They’re rebuilding the world and finding meaning in their lives. I’d just rather act before all that suffering.

So, can nature heal? I think it can if we’re willing to let it.

How can we change?

For better or for worse, changing our relationship with nature is less about technology and more about attitude. For much of history, especially in Christendom, we preached the theology of dominion, killing whatever we wanted because we owned nature; it was our birthright. In the US, we wiped out entire species – not to mention the wanton genocide against humans that was part and parcel to Manifest Destiny. If we want nature to heal, then, we have to change how we view it. Nature can’t simply be something to be exploited. It has to have rights, lines we won’t cross simply because it’s wrong. We’ll talk more about the growing movement around biodiversity in a later piece, but the first step is challenging ourselves to let parts of nature heal, to create places that belong to everyone and no one.

Further Reading

- Here’s some helpful FAQs from Open Lands about taking care of the trees in your own backyard

- Watch this video for tips on how to make a pollinator-friendly garden

The Train

The train rumbled through the darkness, cold night air whooshing through my open window. In the dimmed night lights of the car, it felt like there was no distance between inside and out. I was part of the landscape even as I sped through it, the tree branches seeming to reach for me in the moonlight. A part of me wanted to reach back, to disappear into the night. It felt like a dream, like I’d left everything behind.

Unfortunately, moments like that are fleeting. They’re essential, this sort of…distilling of the world’s beauty, but reality always comes knocking again, demanding to be served. As much as I wanted to commune with the beauty of the universe, to enjoy the thrill of being on a train after so many years, I was still just one thing, one man. The air outside was chilly with fall, and sooner or later, someone would complain about my open window. So, I took one last deep breath of cold air and stood, shutting the window as I stretched.

We had hours to go yet, but I’ve never been any good at sleeping sitting up. Generally, I need a full night’s sleep, and I was sure I’d pay for it in the morning, but I’d long ago dropped my anxiety around missed sleep. During the dark years, when things were at their worst, I’d usually spend two nights at a time pacing the halls with worry, only to sleep like the dead on the third night, finally paying off some of my sleep debt. And finally, I’d learned how to, if not thrive, at least survive without my rest.

I’d heard there would be sleeper cars on the new high-speed trains, but there was little chance of me affording one. Besides, even with how much the economy had recovered, were we really ready for differentiated tickets? I suppose someone must be making money out there, but there were enough of us still living on refugee credits I couldn’t fathom how they’d fill the rooms. Still, I suppose luxuries of any kind were a good sign. Even if I couldn’t afford them, it felt…freeing to know they were out there. If we had the resources for them, it meant the end was no longer so near.

It must be what it had felt like in the early 1900s when people first saw cars. There’s a sort of wonder at the possibility of something new, even out of grasp, assuming, at least, that its magic might reach you eventually. Of course, the rampant inequality of the Gilded Age had bred the Bolshevik Revolution, but today, I decided to feel hopeful. Maybe we’d do things right this time. Maybe I’d be surprised. After all, even if it wasn’t high-speed, I was on a train. Hell, I was on vacation, and that felt like a miracle.

I’d been in the Reconstruction Corps, of course, so I’d traveled, but this was different. I hadn’t traveled for fun in fifteen years. In the corps, you stuck with your crew, herded like cattle from one site to another, with only more desolation waiting for you on the other side. This trip was entirely mine, a blank page, a map with no edges. Even with an itinerary and a ticket paid for months ago, there was something about traveling alone that felt like anything could happen.

I went into the dining car, where there were still a half-dozen people milling about. There were a few couples, all in their own quiet conversations, heads bowed together, with a few stragglers sitting at the bar. Even though the bartender was dressed no differently from me — standard issue recycled wool pants and a hand-sewn shirt — he had the look of a professional about him, his sleeves rolled up and a towel over one shoulder. He didn’t move from the back of the bar, his arms folded before him, but he smiled warmly, nodding his head toward an open stool.

I sat, the cushion oddly comfortable. It looked like leather — salvage, perhaps? Unless those leather cloning facilities were already operational, though it seemed a bit…wasteful, even on vacation.

“What can I get you?” the bartender asked.

“I…don’t know,” I said, suddenly paralyzed by the array of bottles and jars behind him. It wasn’t just a bar, there were snacks and things, but that didn’t make it any less overwhelming. Each bottle was a glowing gem, and I some wayward robber who’d gotten into the vault.

“First vacation?” the bartender asked gently.

“Is it obvious?”

“Not terribly, no,” he said, reaching for a bound menu. “But everyone goes through it. It’s just been too long for most of us. Here, this usually works.”

He flipped to the back of the menu, his movements precise as he found the page, turning it toward me. I picked it up, staring at the hand-drawn image of a bowl, a mountain of color rising from its top.

“Ice cream?” I asked, his smile widening at the shocked look on my face. “Like, real ice cream?”

“Well, define real,” he said, leaning to open a freezer by his knees. “It’s kelp-based, but after all these years, I can hardly remember the difference myself. It’s not bad, and we actually have more than one flavor.”

I forced my mouth closed, wiping it absently — even if the drool was only in my head.

“How many credits is that, though? I only have so many for the trip and…”

The bartender raised his hand, cutting me off.

“Comes with the price of the ticket,” he said. “You get one snack, one drink, and breakfast in the morning before we arrive — though they’ll bring that around on the cart. So, what flavor?”

They were written on the carton in what had to be the bartender’s curling hand. Strawberry, vanilla, and chocolate. It would have been so basic before, but now, seeing chocolate alone was incredible. I’d finally gotten used to coffee being back — ignoring all the complex physics of international trade that went over my head — but an entire carton of chocolate ice cream? It was baffling.

“Strawberry,” I said before I could change my mind. I might regret not saying chocolate later, but it felt like a bridge too far, like I might wake up from my dream if I flew too close to the sun. Besides, there was always the train ride back, wasn’t there?

“Hmm,” the bartender hummed, nodding to himself as he pulled one of the cartons out. Was he surprised by my choice? Did I not look like a strawberry man? Either way, I was too mesmerized to care as I watched him place a perfect sphere of strawberry in a beautiful glass dish.

“Anything to drink?” he asked as he placed it in front of me, a dainty little spoon lodged into the side of the strawberry mountain.

Now my mouth was dry, and I had to unstick my tongue.

“Umm, no,” I said. “This is good.”

“Water?” he asked, pointing with his thumb at a large green tank at the end of the bar. How long had it been since someone casually offered me water in a restaurant? Twenty years?

He followed my eyes, chuckling.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t think I’d be blowing your mind so much. Seriously, we have plenty. The train runs on hydrogen and this filters in from the fuel cells. The cell is ceramic too, so it’s fine to drink.”

“Oh, well…a glass of water, then. Thank you.”

He placed an equally perfect drinking glass in front of me with a nod. Then, his job guiding a clueless traveler done, he retreated to the other end of the bar.

I didn’t want to let the ice cream melt — was actually terrified I’d somehow ruin the experience for myself — but the water was just as captivating. It filled the glass like a tiny ocean, taking on a golden hue in the candlelight. I reached for it, taking a slow, careful sip. I thought it might somehow taste like an engine, but it was perfect — cold and clean, like it had melted from an icicle.